Tommy Lokey: Consummate Jazzman at The Church Studio

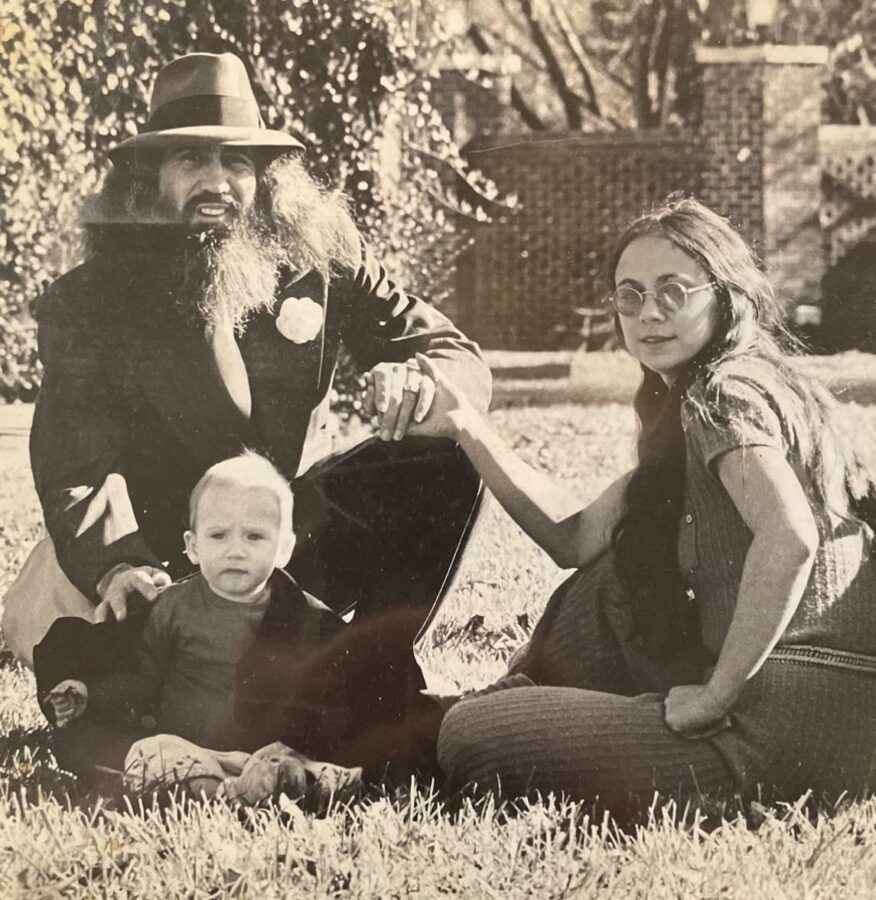

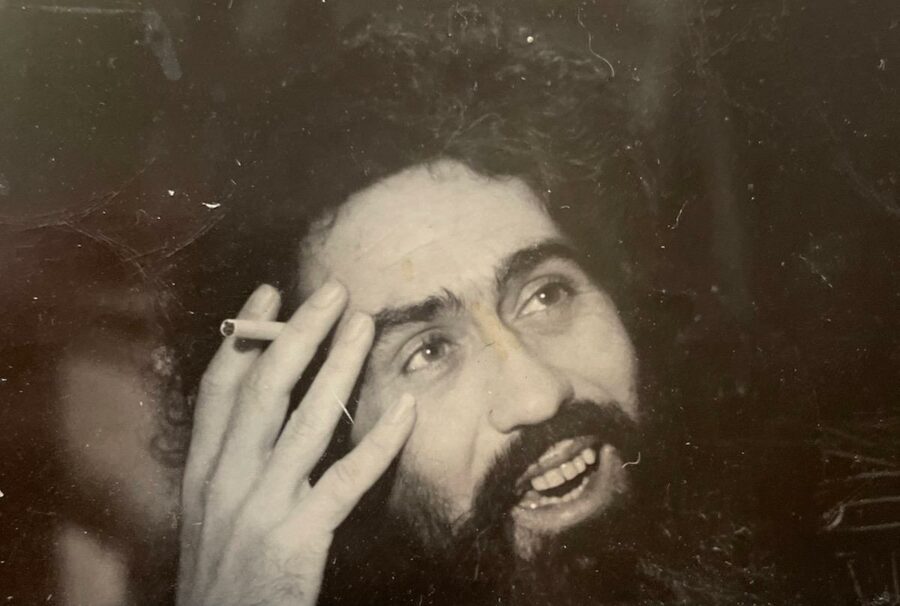

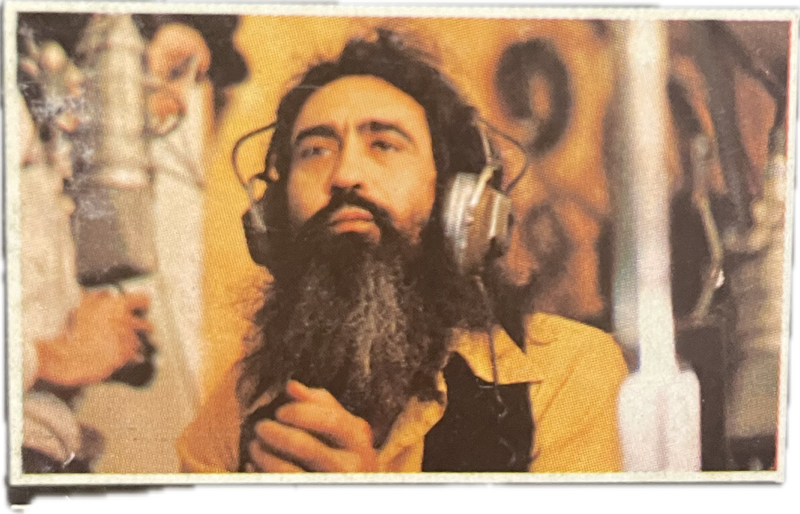

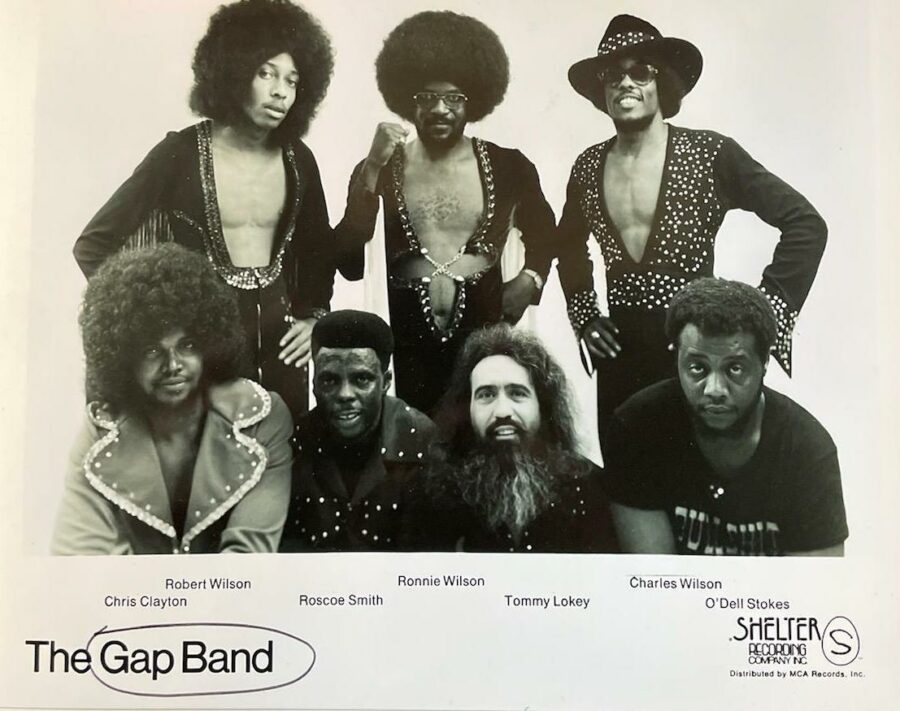

Although few in the current Tulsa music community would know his name, in his day, Tommy Lokey was a local legend. Today, you can find a few 1970’s Shelter Records publicity photos of a seven-man funk band that included him. Tommy is the sole white guy, with a wild mane of dark hair and a sprawling beard. That band was the Gap Band, and Tommy Lokey was a founding member.

“They used to practice in the living room of our house over at 15th and Elwood,” said daughter Carole Lokey Ruffin. Although Tommy did not remain with the band into their great successes in the 1980’s, he was there in the beginning at The Church Studio. His presence was actually something of a coup, for Tommy, with his trumpet, was then considered to be one of the truly premier jazz musicians in Tulsa and still is by those with long memories.

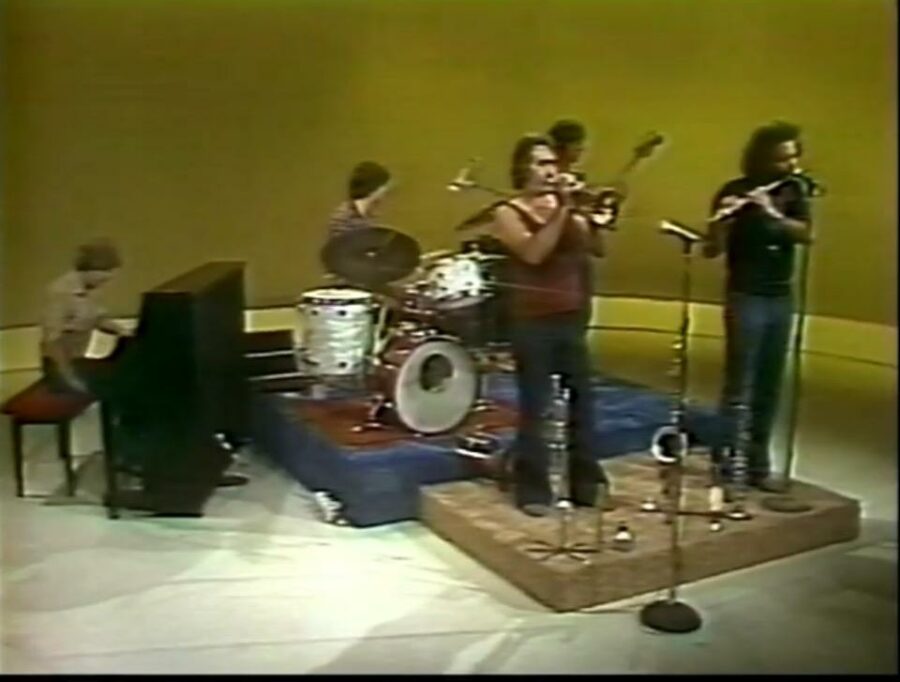

Tommy can be seen playing live on film at The Church Studio with Leon Russell and the Gap Band in a session from 1974. “Here’s the jazz part,” Leon would say, introducing Tommy’s solos. The Gap Band recorded with Russell on the album Stop All That Jazz, released the same year, and Tommy, as well as Gap brother Ronald Wilson, played a major role in six of the album’s 10 cuts. For one example, their presence is notable in the title tune, where the lyrics seem to protest against jazz but which the horn lines repeatedly interrupt. It is a kind of extended joke (as is the album cover), with Russell offering his rolling, choppy “blues” piano as an antidote to Tommy and Ronald’s fluid offerings. Tommy’s prolific skills are particularly showcased in an expansive solo on the cut “Smashed.” Tommy and Ronald’s extensive contributions are noteworthy in that Leon seems to have incorporated horns on only one other album in his entire career, making Stop All That Jazz unique.

The Gap Band also toured with Russell in 1974, playing 18 dates. Tommy even brought his wife Gwen and newborn son Eden along, who it was said would actually be sung to sleep to the wild rocker that formed part of the set, “Jumpin Jack Flash.” At the end of the tour, Leon played at the Tampa Jam, which included Ike and Tina Turner. People told Eden later that Tina made a big fuss over him.

In 1974, the Gap band’s first album, Magician’s Holiday, was also released on Shelter Records. Tommy wrote two songs: “I Yike It,” a jazz-inflected funk tune that opens the album, and “Tommy’s Groove,” a fully instrumental cut with a prominent trumpet solo. Tommy also appears on the 1977 release, Gap Band. Done on the [Tattoo] RCA label, it includes Leon Russell as well as Chaka Khan and James Cleveland, leading a gospel choir. Tommy’s credits here include two songs co-written with two of the Wilson brothers, “Knucklehead Funkin,” with Robert, and “Thinking of You,” with Ronnie. “Knucklehead Funkin” was also chosen for the album Strike a Groove (Passport Records, 1983), a collection of the band’s strongest songs to that date. In 2020, “I-Yike-It,” performed by Charlie Redd and Briana Wright, was selected for inclusion in the extensive collection Back to Paradise: A Tulsa Tribute to Okie Music (Horton Records).

Tommy also supported others in the recording studio. One was Steve Gaines, subsequently guitarist with Lynyrd Skynyrd, on One in the Sun, partially recorded at the Church Studio in 1975. Tommy and Ronnie Wilson both played on Nannette Workman’s 1977 album, Nannette Workman, sung entirely in French. Workman would become an international star and be elected to the Mississippi Music Hall of Fame.

In the 1970’s Tommy Lokey was an integral part of the founding and development of Tulsa’s Gap Band. But what brought him to The Church Studio had an intriguing genesis many years before.

Born in 1935, Tommy was something of a child prodigy on the trumpet down in Henderson, Texas. He was raised in a very loving Christian family; his parents were always called “Mama and Papa Lokey.” His tie to the faith would play the greatest role in his life in his last years. In elementary school, Tommy won a contest in Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour, playing the dizzying “Flight of the Bumblebee.” He continued throughout his school years, and by his teens, he was an exceptional trumpet player. He followed his formal education at Kilgore Junior College and subsequently received a music scholarship to the Lamar Tech Institute in Beaumont. But it was next door in the big city of Houston, at a club called The Purple Onion, that Tommy heard jazz close-up for the first time. The Onion was the type of venue in which he would ultimately shine himself. Some speculation exists that during or after junior college, Tommy began to play professionally, even touring. Tommy, however, left school behind and joined the army in 1956 at age 21, for reasons unknown. He was sent to France and stationed at the old, renowned fortress of Verdun, from which he would sally onto the army parade ground every day for two years and play “Reveille” and “Taps.”

Tommy did not fit in the army. His younger brother Bob said he was “a hippie before they ever arrived, a beatnik, I guess they called them back then.” It is no surprise that Tommy soon began making periodic escapes from the parade ground to the clubs, the realm of jazz magician Miles Davis. Davis toured Europe in the mid to late 1950’s, and Tommy went to see him in Paris every chance he got. In fact, Tommy’s idol appeared to have once recognized his talent. His son Eden recalls a story about his father once playing some lines for Davis after a set, who was perhaps inclined to be dismissive. But upon hearing Tommy, Davis remarked, “Well, the man is a trumpet player.”

Tommy finished his tour of duty in 1959 and returned to the States, now with a French wife and two stepchildren in tow. His family had moved to Drumright, Oklahoma, and Tommy took on the task of cleaning out petroleum tanks there in the “wildcat” oilfields, to which he would return from time to time in order to provide for his new dependents. But music was his desired career, and Tommy started by moving away from Oklahoma. He eventually landed in San Francisco, with its lively jazz scene, where he honed his chops in clubs from 1962 to about 1965. His son, Thierry, remembered that he worked during the day and headed out to play night after night.

Tommy’s overall professional activity upon returning to the States remains shrouded in mystery. He made surprising connections, which included playing in Count Basie’s band. Eden recalls a story of how his father was ridiculed by none other than Don Rickles in Las Vegas. “Who let the Mexican mafia guy in here?” demanded Rickles (Tommy’s coloring was dark, “Mexican” was the best description others could come up with – and his attire could be unusual). Basie reportedly came down from the bandstand and said, “Don’t you talk to my trumpet player like that.” Rickles tipped Tommy a day’s wage at the end of the night.

Tommy must have toured with many other artists of different styles during the 1960’s. Thierry recalls him gone for some days at a time in California, perhaps supporting visiting acts. Daughter Carole Lokey Griffin asserted that “he played all over.” Eden remarked, “I remember him rattling off a long list to me once. I was too young to know who some of them were, but other family members or others did. I remember Sam Cooke and Buddy Miles mentioned – even the Rolling Stones.”

According to his kids, Tommy was later reeled into a true phenomenon: the 1970 Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour. Perhaps they had needed another trumpet player and picked him up along the way. Tommy’s sometime practice of including family on the road lends this possibility some credence. Eden claimed they saw his mother in the Mad Dogs film. “She was getting off a tour bus,” he said.

The question is: why did Tommy leave his base in California and earlier touring, to return to Oklahoma? One story is that Tommy was lured to Tulsa by jazz entrepreneur Sonny Gray, who owned the Rubiot on South Peoria Avenue. He had heard Tommy somewhere – one account places it in Texas, while another probable tale may be on a San Francisco night or somewhere else – and snagged him.

From wherever he had come, it was immediately recognized in Tulsa that Tommy was indeed something special. The specific time when he appeared is unclear, but the jazz scene was wide and active in the 1960’s and beyond. Tommy was soon being noticed all over. Tulsans would know, among other venues, the Rubiot, The 9 of Cups, Magician’s Theater, Boston Avenue Market, the Cognito Inn, and several of the big hotels. He played at Skelly Stadium in Ken Downing’s big band as well, and in prolific after-hours gatherings at venues in Tulsa that many avoided. The combos he was in included the well-known Tux Band and the jazz quintet Essence. He played with everyone in town, in particular Bill Crosby and Susan Gray, and Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame inductees Tommy Crook, Pam Van Dyke, Sonny Gray, Rudy Scott, Mike Moore, and George Dennie, among many others.

Tommy Lokey’s performance was considered absolutely first-rate, with acknowledgment of it falling almost perfunctorily from colleagues. David Teegarden, drummer with Bob Seeger for years, sat in with Tommy at the Rubiot a number of times. “He was just a wonderful player,” he volunteered. Collaborator Dave Reynolds said, “I was the drummer in the Rubiot in the mid-60’s in Tulsa, and Tommy would come in from the oil fields where he was a wildcat worker all week, and it was one long, beautiful jam all weekend.” Tulsa trumpeter Gary Leming put it this way: “He could get more out of fewer notes than anyone I’d ever heard. And when he was on, he could take your breath away.” Rudy Scott, an Oklahoma Hall of Fame inductee, stated it succinctly: “That trumpet player, Tommy Lokey, that dude could really, really play.” And jazz pianist Falkner Evans, who began in Tulsa, eventually recording seven albums, commented to the Tulsa World, “Tommy was just one of the most heartfelt players I ever met; I play with guys up in New York who could’ve learned from him.”

With apparent contacts such as Count Basie, other professionals far from Tulsa must also have been aware of his excellence. In addition, Tommy received notable acclaim from those prominent in the academic field, which he never saw again after junior college. This included professor Dan Hearle of the renowned jazz program at North Texas State (now the University of North Texas). Hearle referred to Tommy as the “Mexican Miles.”

Bassist Jim Bates, who played 40 years in the Tulsa Symphony, taught in every college in Tulsa, and has played everything, from jazz, rock, pop, and country, most recently with The Tractors at The Studio, played with Tommy many times. “Tommy could fit into any situation and adapt to any kind of music; it didn’t matter what it was. That’s easy on a bass, but not on a horn. And Tommy could make any band good.” Bates went on: “Tommy was like the greats—Miles, Getz, those guys. There are many very good players, but with Tommy and his improvisation, you always knew it was him. He was that unique.”

Hall of Fame member and 50-year veteran of regional jazz music, Mike Moore, with both academic (Ph.D.) and professional credentials, including 40 years as director of the Modern Oklahoma Jazz Orchestra, provided further testimony to the Tulsa World. “Really, on a good night, he was as good as anyone I’d ever heard from anywhere. I could be walking down the street and hear a band playing up ahead, and if it was Tommy Lokey playing, I could tell immediately.” Moore’s combos have played with national and international figures, including Oklahoma’s own jazz legend Chet Baker and rocker Lee Loughnane of Chicago. His big band has performed with comparable figures. But Moore saw Tommy as far deeper than any performative expertise. “He was kind of a very spiritual, guru-like figure, a Jazz Buddha mentor in the jazz community. He was very much into the spiritual as well as the technical part of jazz.”

When later asked what he meant by the “spiritual” aspect of Lokey’s investment in jazz music, Moore explained, “Tommy had great respect, a reverence for music, for jazz as an art form, and he felt that the ability to perform it needed a serious commitment. It was like a gift given that had to be handled carefully; its roots were original, spiritual, and greater than any particular aspect of practicing it. What you play has to be authentic. Improvisation in particular is an expression of yourself; it has to be real, as if representing a life, your life, and the story you tell as an artist has to be lived. The credibility of your story should stem from living the story you are telling. You have to mean what you say.”

Tommy’s narratives were clearly authentic, and he encouraged the development of that living quality in younger players. A budding trumpet player himself, Moore shared the combo stage with him at times and recalls one moment descending a bandstand to noisy acclaim from an impressive solo. Tommy’s direct but gentle admonition was, “You played so much trumpet. When are you going to play so much music?” Bandmate Dean Demerritt recalled Tommy’s striking presence, extolling his performance as “soulful, lyrical storytelling. And Tommy never ‘mailed it in’; he was always present; he gave it his all every time.” Tommy Lokey’s commitment to compatriots was deep, and his stories in sound were universally recognized as exemplary.

That exemplary quality extended to Tommy’s character in general. “He was a true gentleman,” insisted daughter-in-law Lacey LeGall. Thierry added, “He just loved people, having them around all the time, listening to records, and talking about music late into the night.” Carole Lokey Ruffin, who maintained an unflagging insistence on his artistic achievement, spoke of her father with glowing affection, referring to herself her entire life as “Daddy’s girl.” Daughters Maria and Chelsea recalled him as also very intellectually curious, with a marked desire to share his wide and deep interests with them. But most centrally, both acknowledged that he was unusually empathetic and generous.

His musical colleagues amply attested to that personal generosity. “He was just a beautiful cat,” Evans told the Tulsa World. Jim Bates encapsulated Mike Moore’s contention that improvisation represents a lived life, a person’s character. “You play like your personality, and Tommy was a lovely person, so sweet and kind. One time we were playing, and the drummer was really, kind of terrible. The club owner said he had to go. It was Tommy’s job to fire him. ‘I just couldn’t do that to him,’ he said.” Ken Baird, a younger, subsequently accomplished player, commented, “What I most remember about Tommy is how genuinely friendly and encouraging he was to me, a complete stranger.” Mike Moore spoke of being welcomed by Tommy’s wide, open arms to sit in on the club stages when Moore was, as he said, just a college kid. “’Chivalrous’ is the word that comes to my mind about Tommy, and he was that way with everyone.”

Tommy Lokey died in 1999 from pancreatic cancer and was given a memorial service, which received extensive coverage in the Tulsa World. Ronnie Wilson was at the funeral; he turned and played soprano sax to Tommy in his casket as a final tribute. Tommy’s physical life ended there, but courtesy of the internet, you can still see slices of his “live” performance or hear him on audiotapes and the Russell/Gap Band recordings, vivid, if limited, testimonies of his achievements.

In 1976, Tommy’s group Essence did a session at KTUL Television Studios. It is worth noting this venue. It is unlikely that a major television studio would record many local music groups, which may reflect Essence’s noticeable presence in Tulsa during those years. One significant indication of his professional recognition can be heard in recordings entitled “Tommy Lokey Sessions,” done at Sonny Gray’s Studio in 1979. He played beautifully on the trumpet, flugelhorn, or mellophone.

Tommy received an accolade rare for most performers as well: a song dedicated specifically to himself. This was “A Lokey Groove” on Level Playing Field, by former Tulsa compatriot Falkner Evans. It was produced in 2002, three years after Tommy’s death.

The last tribute to Tommy’s efforts could be said to be one of his own, on gospel artist Danniebelle Hall’s Christmas album He is King, according to his family, a work of which he was particularly proud. In later years, Tommy would know or play with other gospel figures, including Andrae Crouch and trumpeter Phil Driscoll. It is particularly interesting that He is King was recorded in 1973 and released in 1974, during the time he was actually working with Leon Russell and the Gap Band. Tommy’s spiritual roots seem to have remained in place during some of his heaviest involvement in secular music.

Gospel was the last music Tommy would play. By the late 1980’s, needing to leave behind the clubs and their destructive temptations for him, in his own words he “rededicated” his life to God. “That saved his life,” one Tulsa colleague remarked. Thereafter, Tommy played almost exclusively in church. At the First Assembly of God in Skiatook, the theretofore unknown Tommy Lokey astounded them. Deacon Jerry Ridnour said, “He would play wonderfully on anything.” Sister-in-law Diana Lokey remembers often whispering to Tommy, “What should we do for the offertory?” With tears in his eyes, he would say, “I’d Rather Have Jesus.”

During those years Chelsea says that her father would pray with her when she was troubled, helping her to find healing – “He was a champion for me when I truly needed one.” He repeatedly called Maria and sang the entire chorus of “I just called to say I love you.” “His voice was lovely, just like his trumpet,” she said. Elsewhere, he always played “Happy Birthday” for all every year, and the kids recall him scat singing with them in the car. But Tommy would continue to play his horn without ceasing; Eden recollects calling his dad on the phone at home, inevitably interrupting him at it. He retains his father’s trumpet. “The keys are practically worn off,” he remarked. And Eden once heard him reminiscing about the old days, playing “Taps” alone in his room.

It had been a long journey from Henderson, Texas, to the parade ground at Verdun, with stops in Paris clubs, San Francisco, national touring, and perhaps even Mad Dogs. But it was during the years in Tulsa that Tommy found his place to truly shine as an artist, in a career amply testified to as superlative combo jazz musician and featured jazz soloist, rock session horn player, and gospel performer both in studio and out in his finally chosen venue, all altogether demonstrating his versatility and artistic stature. The tributes of fellow musicians themselves solidify his character as a consummate professional, an exceptional player, and a genuine individual whose musical gifts it was the good fortune of the community of Tulsa, Oklahoma, to receive.

And at Shelter Records were Leon Russell and the Gap Band, for whom this renowned musician was a co-founder, performer, and songwriter/arranger. Tommy Lokey’s formidable presence made its own special contribution at The Church Studio.

David Deller: Gratitude is extended to the colleagues, friends, and family of Tommy Lokey for their contributions and kind assistance.