THE BILL DAVIS INTERVIEW

By Steve Todoroff

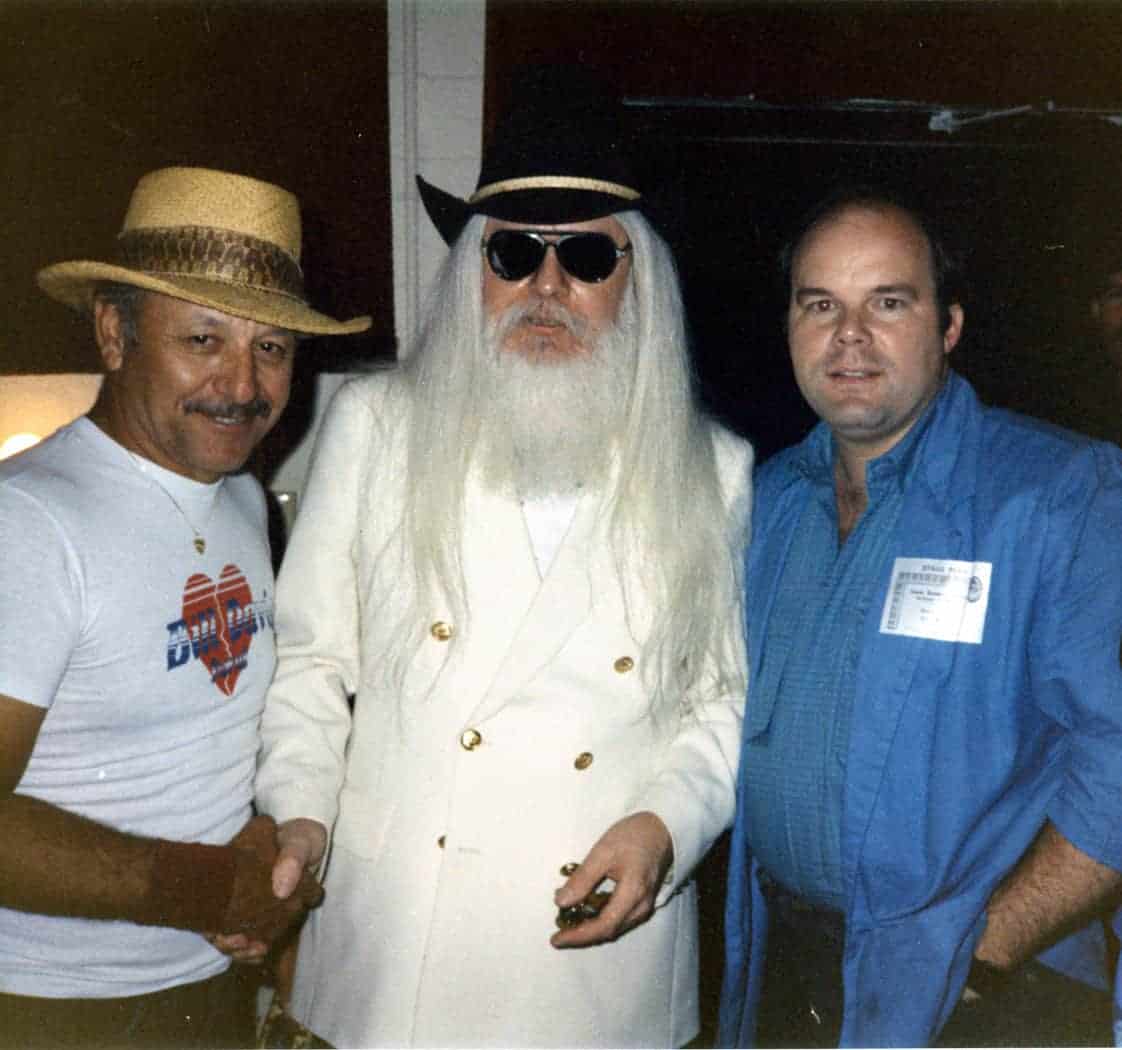

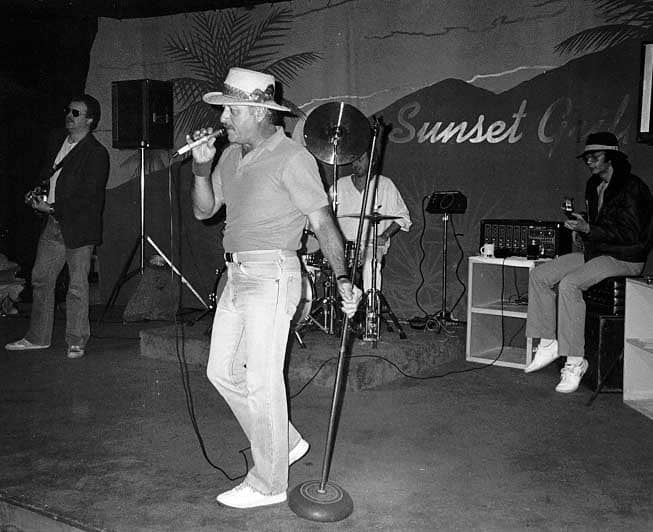

It’s a late September night at the Sunset Grill, a combination cafe/night club in Tulsa where eager fans begin to cram themselves around tables near the vicinity of the dance floor. As they mingle about, a party-like atmosphere maintains them until that moment the band squeezes onto the tiny stage and starts pumping out a beat that will somehow get everyone moving, though by show time there will hardly be room enough to breathe. Ace drummer David Teegarden takes the stage first, double checking his drum setup. He’s shortly followed by bass player Gary Cundiff, who likewise makes sure his equipment is in working order. Before the real show can began, ex-session guitarist Tommy Tripplehorn rushes in just in time to quickly strap on his vintage Stratocaster and lights up a cigarette. By now the real star of the show has made his way up to the microphone, and begins to evaluate the audience, nodding as he acknowledges a few familiar faces. Then it begins. With precision timing and simple, but knife-edged arrangements, the band kicks in as the singer wraps his soulful voice around the first few lyrics. It’s show time for the hyperdriven Bill Davis, who after thirty years, is still living up to his legend.

The durable vitality of that legend is as visible today as it was those many years ago. Catch Davis’ act on any given night and you’ll see the same occurrence: Davis tossing an array of soul titles at a frenzied audience who can hardly contain the beat. Even after all this time, Davis has maintained an ever expanding core of loyal followers, as well as a topnotch crew of players. This alone is a tribute to the man many call the “soul” of the Tulsa music scene.

To commemorate Davis’ thirty years as an entertainer, longtime friend and freelance writer Steven Todoroff, a native of Bixby who now lives in Los Angeles, interviewed Davis on 12/26/89 at Magnolia’s Restaurant, a popular south Tulsa eatery. In the interview, Davis discusses his musical influences and style, his association with some of Tulsa’s finest musicians (past and present), the history of the “Tulsa Sound” and why, after all these many years, he never left Tulsa.

Todoroff, who has researched and collected material on Leon Russell and the Tulsa Sound, first met Davis at the tender age of ten, where he used to linger at the meat counter of Jessee’s Market in downtown Bixby, listening to Davis sing and tell stories about the Tulsa music scene while he went about his butcher chores.

Steven Todoroff: “Live” at Magnolia’s, the day after Christmas, nineteen hundred eighty-nine, with Mr. Bill Davis! Boppin’ Billy, the King of Silly!

Bill Davis: It ain’t Vanilli, it’s Billy! Hey, Walt [Richmond] came out last night and played some piano at a pretty good little deal. Jimmy [Markham] was singing, Don White was playing guitar, I was singing and Jimmy Karstein was playing a little stand up cocktail percussion, you know, the brushes. Boy, it was too good!

Todoroff: Where did you guys play at?

Davis: Over at Emily Smith’s. We had about forty-five people for a little evening get together.

Todoroff: Sounds like it was great fun.

Davis: Even made a little greenback dollar.

Todoroff: A little “dough-re-me”?

Davis: Yeah, a little “dough-re-me” for Tommy [Tripplehorn] and I.

Todoroff: The “Tulsa Mafia.” Some that went on to bigger and better things, and some are still like yourself — refusing to leave town. Singing and playing golf. [Laughs]

Davis: You got it! [Laughs] I like the lifestyle of being at home and still being in music, but not being out on the road. I never did like it, what little bit I did. I couldn’t wait to get back.

Todoroff: Back home to Tulsa.

Davis: Yeah! I mean, I like to be out, you know, when I’m home I don’t like to just sit around the house, but I wouldn’t like to get with five other guys and go anywhere for very long.

Todoroff: Most of the guys in your band, with maybe the exception of [Gary] Cundiff have probably had to do that in their life.

Davis: Yeah, but Cundiff did go to Germany with Jim Byfield on that Brothers of the Night deal. I’m not sure, but I think that’s the only time he’s been out on the highway.

Todoroff: When did you hook up with the guy’s you’re currently playing with? You’ve probably known them for years.

Davis: Yeah, I think Tommy and I have been together over twenty years. I started in ’59, so this is thirty years for me. I guess it was maybe about ’65 or ’66 when I first started playing with Tripplehorn. And [David] Teegarden was playing there with the band for awhile too.

Todoroff: Was Tommy playing strictly guitar back then or was he playing keyboards too?

Davis: He just played guitar. He never plays piano if there’s anybody else playing. If there’s drums and bass involved he’s gotta play guitar because he thinks he can’t play loud enough, so he has to play something he can crank up.

Todoroff: He does well on the keyboards, at least I think so anyway.

Davis: Yeah, he’s terrific.

Todoroff: Most of your band at one time or another has played with somebody else, somebody maybe a little higher profile…

Davis: Well, they’re all road guys.

Todoroff: …or studio and road oriented.

Davis: They would leave town in a minute, and did! As for me, not only did I just not get a call, I never put myself in a position to get a call. I never did advertise that I was about to go anywhere. [Laughs] I found a market here in town for the kind of music I did. I don’t know, it’s like trying to get a record deal. Man, there’s so many good singers a lot better than me that can’t get it out there, so I didn’t see I’d have a whole lot of a chance to go out there and catch any kind of major money, which is the only thing that would get me to go out there. And I don’t know if I just didn’t want to work at it or what. I found I could make a fairly decent living in Tulsa. Shoot, I never did desire to go out of town.

Todoroff: Well, like you said the other day, you could starve just as well in Tulsa as you could anywhere else.

Davis: That’s right. [Laughs]

Todoroff: I remember one time, and correct me if I’m wrong, in the early or middle Seventies, when you headed off to Memphis.

Davis: Yeah, I did. I went to Nashville. I think that was in ’75.

Todoroff: You went to Nashville?

Davis: Yeah, I stayed all summer there.

Todoroff: What all did you do, write songs and peddle them around?

Davis: I pitched a few songs.

Todoroff: Did you get involved in any sessions or anything like that?

Davis: Not to any great degree. I spent some time in the studios around there but it wasn’t with any goal in mind, it was just hanging around watching. It was just kind of a vacation. I wasn’t going up there as an entertainer, I just went up there because I had some country songs I had written.

Todoroff: I expected during that period to read in the paper where Elvis had recorded a couple of your songs or something like that.

Davis: Aw, really?

Todoroff: Yeah, you know, the “Eddie Rabbitt” Syndrome.

Davis: Well, Delbert [McClinton] has cut a couple of them, and Teegarden and Van Winkle has recorded a song on one of their albums that Tommy and I wrote years ago. They all liked it. When [Jamie] Oldaker was on the road with Eric Clapton he said that Clapton would play my tape all the time, out of all the tapes back there in dressing room. So I’ve had a lot of respect from guys I’ve never met before. Somebody said they were in England and they were over at Stevie Winwood’s apartment and my name and Tripplehorn’s name came up in the conversation. [Laughs] So my name’s been blackguarded around the hemisphere.

Todoroff: That’s pretty amazing. You’ve got to believe that will come back home to you in spades one of these days.

Davis: Well, I’ve put so much time and grade in on this career of mine that I’m sure that the word’s got out here and there that there’s a real Bill Davis in Tulsa that you ought to hear if you like this kind of music.

Todoroff: What was the statement that singer Delbert McClinton said about you, that your, “The best undiscovered blue-eyed soul singer in the world?”

Davis: Yeah, a lot of people think, “He doesn’t have blue eyes!” [Laughs] I finally met Bonnie Raitt for the first time and she had known of me from tapes she’s had out there in California.

Todoroff: And of course, Bob Seger’s probably heard a lot about you.

Davis: Well, he’s been out to the club and listened to me. I’ve spent some time just sitting around and talking to him. He’s just an old hillbilly like me.

Todoroff: It could just as easily have been the other way around with you two, under different circumstances. He just happen to catch somebody’s ear and got a record contract.

Davis: Plus, he was raised in a lot bigger market. Detroit is bigger than Tulsa and Bixby! [Laughs] I believe if I would have had this same act and same talent and was in a place where I could have showcased it like Miami or Las Vegas, it could have been different. I always felt like I could have made a good living in Vegas if I had wanted to go out there. You don’t necessarily have to have a record deal to be a good entertainer, or have a record deal to make mega money.

Todoroff: I guess one of the big advantages out there, say in L.A. for instance, is the demos, commercials and other recording dates. There’s always that Union check waiting on you over there. When Leon Russell went out to Los Angeles and broke into sessions, that’s how he lived. He’d go by the Musician’s Union hall in Hollywood once a month and pick up a stack of checks from all these sessions he played. Sometimes he had a couple of thousand dollars or more waiting for him to pick up.

Davis: Really? That was a lot of money in the early Sixties.

Todoroff: It sure was. Now you were born in Tulsa, weren’t you?

Davis: Yes I was.

Todoroff: Isn’t there a little story behind the hospital where you were born?

Davis: It was a block and a half from Cains Ballroom. I used to hang out at Cains all the time and watch Bob Wills set the folding chairs up for the Saturday noon broadcast on KVOO radio. I’d get a free concert, watching Leon McAuliffe and all those dudes up there playing. I guess I absorbed a lot of that, you know. I’ve always liked ballrooms and stuff like that.

Todoroff: Tulsa’s certainly had their share of them over the years.

Davis: I always liked to play the Brady Theater too.

Todoroff: The old Magician’s Theater had that “feel” to it when it was around. You graduated from Central High School didn’t you?

Davis: Yes, from what is now the Public Service Company building.

Todoroff: J.J. Cale went to school there too, didn’t he?

Davis: Yeah, J.J. and I went to school together for three years. I think he went to a different junior high. I went to Roosevelt and I’m not sure where he went.

Todoroff: What year did you graduate?

Davis: 1956. Walt Richmond came out the other night and said he was at a flea market and found a 1955 Tom Tom yearbook from Central with Cale and I in it. It’s really weird. Those guys that now live in California got up and played with me last night and it’s that same disciplined, don’t-add-a-bunch-of extra-licks type playing. I don’t know if you’d call it the “Tulsa Sound” or not but is sure is clean. These new guys, I call them “gunslinger” guitar players, they just can’t play it. They can’t seem to leave their hands quiet long enough to play it.

Todoroff: They don’t have tasteful chops.

Davis: That’s right. Somebody came up and talked to me when we were playing a jam session at a club and told me that I was his favorite band because I’ve got that “open” sound, which means a lot of the time there is nothing going on. You play your note, you play your chord, whatever, but it’s those pauses that makes it what it is. I guess that’s what you would call the “Tulsa Sound.” It’s not cluttered with a lot of technique and stuff, as much as it is just timing and keeping it right there in that pocket.

Todoroff: I’ve heard that before. I believe it was Ellis Widner of The Tulsa Tribune who wrote sometime back that the “Tulsa Sound” was “minor key blues-type tunes with few chord changes throughout.” Just clean and simple, like you said.

Davis: Well, it’s just an attitude. When I think of “Tulsa Sound” I don’t think of rock and roll so much as I do just simple three chord songs. It seems like that’s the downfall of a lot of bands. Well, maybe not their downfall, but there’s a lot of bands that hate that stuff. They think the “Tulsa Sound” is a wet blanket on Tulsa. It just absolutely bores them to death. It’s just the idea of that’s how you want to play it. Like Walt Richmond and all those guys, those real good players, they can play anything you want but whenever they write or when they play with me, it comes along like there’s nobody showing off. Club One has a jam every Wednesday night that I’m involved with and it seems like every guitar up there tries to play faster than the guy that just sat down, and it’s just one continuous, you know, wahhhhhhhhhhhhh! [Laughs]

Todoroff: There is something to be said about just clean, tasteful chops. That’s what Leon Russell’s reputation in Hollywood was too. He didn’t overplay, he played what was needed. Those L.A. producers recognized that too. The same clean Leon licks you hear on Phil Spector, The Beach Boys and Frank Sinatra records are the same ones that he played right here in Tulsa.

Davis: And I think that’s what we always call the “Tulsa Sound.” Now [J.J.] Cale had that concept back in high school when he was making records in Oklahoma City. They were like that.

Todoroff: Were you singing throughout school like Cale?

Davis: No, I’d go out and listen to him, watch him and marvel at it. But it wasn’t until I was twenty years old before I started singing and making money. I could always do it, you know, sing in church, but I didn’t have a band or anything. Since I started I’ve worked steady, I mean the only times I haven’t sung is when I’ve left to take a rest. There’s been a few years in my thirty years of singing that I’ve taken off. I think once I took a year off to open up a bar and I ran it for a year and a half. Now I would sing with bands I had in there but it wasn’t like work.

Todoroff: Was that the one on South Lewis, Sweet Williams?

Davis: Yeah, but it wasn’t like I had a band that I worked with then. I had turned everybody loose. And when I decided to go back to work it was like I had never been away. As soon as I started back to work people started coming right back out.

Todoroff: Well Bill, I have fond memories of you from the Sixties, working down at Jessee’s Market in Bixby. I’d come in there and listen to you sing and watch you cut meat.

Davis: [Laughs] When I got married twenty-five years ago my wife’s dad owned this grocery store and he taught me how to cut meat and be a butcher, which I thought was a good idea. And I still did that periodically until I got my home paid for, then I didn’t feel like I needed two jobs so I just kept singing and started playing a lot more golf during the day. [Laughs]

Todoroff: [Laughs] Nothing wrong with that! Now you’ve seen a lot of people come and go back in the late Fifties and early Sixties when music seemed to be hitting all over. Rock was starting to come out and become popular, and particularly these young groups consisting of mainly white singers without much soul in their repertoire. What were your influences?

Davis: Well, when I first started singing in Tulsa there were only four other bands in the whole town that I knew of, and only four other clubs that had live music. I’d been singing since ’59 and then when The Beatles hit in ’64 it seemed like it just mushroomed. All of a sudden there was fifty bands. Everybody got them a guitar. It seemed like every young kid started playing guitar. When I started it was mostly adults that had bands, there wasn’t any real young guys. I call them adults, they were guys in their twenties like myself. Jimmy Markham. Leon Russell was in town. Chuck Blackwell and Carl Radle were here. The Cimarron Ballroom was going big. We’d go down there and see the big acts of our time. Markham and I went down there and saw Fats Domino for two bucks. Ray Charles had also played there.

Todoroff: I also heard that Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis came in during that period.

Davis: Yeah, they did. I backed up Freddie King a few times when he came through from Texas. I opened up for Bruce Channel back then. I worked with Wilson Pickett. My influence up until ’62 was Bobby Darin. When I first started singing I thought that was the way to do it, you know, to have a bow tie you could untie and unbutton the top button of your shirt and wear a black suit like you were at the Copa Cabana or something. But then I caught James Brown in ’62, and from then on I started singing soul music. It fit what I liked to do plus it was a new idea for a white guy to sound like that. That’s why I work so steady. For years and years I worked six, seven nights a week. A lot of dues. A lot of chops. It’s paid off and laid the groundwork for where I’m at today. I’m not coasting now, by any means, but there’s an unspoken respect I get from even young musicians that just know the amount of time I’ve spent on stage and still doing it. It’s always, “Hats off, Mr. Davis,” you know. I don’t give anybody any advise, but I get a lot of pats on the back from people saying I’m an inspiration. They think it’s a good deal that I’ve hung in so long. [Laughs]

Todoroff: Well it’s well deserved. I still get people asking me when they come into town “Hey man, is that Davis guy playing somewhere we can go watch him tonight?” So I’ll just grab the paper and find out where you’re at that evening, and they’re never disappointed. Now back when you started playing there was Griff’s Place and the Cheri Bop Club, but what else was around?

Davis: There were a few places on Admiral and on Eleventh Street. The Casa Del Club and The Paradise Club.

Todoroff: You played out at The Paradise Club quite a bit with Markham didn’t you?

Davis: Yeah, but back then you would play someplace until midnight, then tear all your equipment down, load it up in the car and drive across town, set it up and play in some nightclub until four in the morning. So a lot of times you go to two jobs a night, start at eight and get off at daylight. And make no money. You’d make seven dollars at one place and ten at the other for, say, twelve hours work.

Todoroff: That is paying dues.

Davis: I can remember it just like it was yesterday when Leon, Radle, Karstein and everybody moved to California. And I thought, “No, not me.” Tripplehorn and all of them went out there and lived with Leon. I mean it was just an exodus of all the top dogs in Tulsa. Took that “Tulsa Sound” concept I was telling you about earlier. That clean, good playing, you know, that “don’t rush into anything” sound. Just a light dusting. But they took it out to L.A. and everybody just loved it. Cale went out there to the Whiskey-A-Go-Go and just stood them on their ear.

Todoroff: I think there’s one exception and maybe he can play the “Tulsa Sound” although it’s more of a sweet, melodic type sound and that’s David Gates. People just cannot believe that he is from Tulsa, and particularly that he played with this same group of musicians we just talked about. And the ironic part is that he’s probably been one of the more commercially successful of the bunch.

Davis: Yeah. Now I used to watch Gates before I ever started singing and he would play guitar and sing at these department store fashion shows for young teens where they would have tea and watch these girls model these clothes. Gates would just stand up there with an amp and a guitar and sing all by himself, working these afternoon teas at the tea room. I was working at one of the stores and I’d just go by there and scratch my head and think, “Well that’s the deal I need to be doing right there.” But I don’t know, I never did get any inspiration from him. I think a lot of his inspiration was Buddy Holly, and I never got into that. I liked early Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and cats like that. I thought Little Richard was the best rock and roll singer that ever lived, in fact I still do. When I finally quit singing Bobby Darin tunes and Rick Nelson and Elvis songs, I started singing Otis Redding and that stuff. I felt I’d finally found my niche because I liked that audience feedback I got. You can bring people to their knees with the right song. You’ll hear them out there just going “Oh Lord, help me, help me!” [Laughs]

Todoroff: Who were some of your first band members?

Davis: Just a bunch of drunks, truck drivers and trash haulers.

Todoroff: And ex-welders? [Laughs]

Davis: Yeah, that same crew. [Laughs]

Todoroff: You kind of upgraded after that, though, wi

Davis: No, I never did do that but I did a lot of down on my knees and springs and do that one-legged walk. And I was really involved in that dance thing, a lot like Michael Jackson. My concept was that you had to look good. It wasn’t until The Beatles hit and all these freaks and longhairs like Frank Zappa and people like that started making records, and I thought, “Well, in 1956 if you looked like that you couldn’t get a record deal.” It was more important what you looked like than what you sounded like. Fabian is a perfect example of that. I mean, they got a guy that looked good, but he couldn’t sing for nothing. [Laughs] Then it got to the point later that it was just the opposite, for example, Seals and Croft. Look how ugly that one guy was. And Art Garfunkel. Then I finally realized, it’s more on what the music sounds like. You can look like anything. There for a long time I was changing clothes three times a night, wearing the different suits. Always wearing tight pants and doing my James Brown routine. Always had my hair just right. And that was real important than. I was into that dance routine, you know, like a floor show or something.

Todoroff: What were the years you were doing your James Brown act?

Davis: Oh, I’d say probably from ’63 to the end of ’73, maybe ’74. By that time I had what you call character in my voice. I’d gotten to the point I could just stand up there and sing. I didn’t feel like I had to dance to entertain and to be accepted, but that was a big part of it. I’ll tell you another guy that used to do that, and that was Roy Head. He’d come into town and he’d get down on the dance floor and nobody would dance. I would do the same thing. People would just gather around the dance floor, like a school yard fight. Everybody in the crowd would just get up from the table and bring their drinks and just form a big circle, five or six deep, standing on their tip toes. And me out there with my microphone, just working up a sweat, boy. Down on my knees, spinning, falling, screaming, hollering and carrying on. I’d get radical. One time I got an old Ampeg brand amp, you know, PA set up, and I had four speakers in these tall columns. I got those columns off the stage and jerked two of them off the wall and put them out on the dance floor, side by side, and I stood up on top of them. And then I’d pick one up on my shoulder like a six foot long ghetto blaster and I’d be singing and spinning that thing and pushing it up. People would just go, “Aaahhhhhhhh, he’s too cold!” [Laughs] For about ten years I was doing that routine, you know, sometimes about six straight songs on the dance floor without stopping, playing about thirty minutes at a crack. Just hard sweating. Guitars going, and the bass and the drums, and me out there blowing my top! That just added to my reputation because everybody knew when they came out they were going to get a good show. It was just an extra effort that the other bands didn’t do.

Todoroff: What’s the strangest thing that ever happened to you on stage? Are we talking Tom Jones here with the panties flying out on stage?

Davis: Yes, there’s always the total nudity, now that’s happened a few times. I’ve broken up fights while I was singing, and never quit singing the song. I wouldn’t hit anybody, but I would go down and get in between them. I’d be singing “Mustang Sally” and holding guys apart.

Todoroff: Let’s talk about your band again for a minute. Every time I take somebody new to see you it just blows them away whenever I start reciting the history of each band member.

Davis: Well, that’s the good thing about getting these good players. They want to play legitimate music and they’re not interested in playing if it’s just going to be with a group of guys that don’t, you know, get off. So that’s why I’ve always had these good musicians. The guys in my band are good enough to play with anybody, and have played professionally on albums and done sessions, and got paid money to fly out and put a guitar track on a Georgie Fame album out in California. So that’s something that a lot of bands don’t have, is the notoriety enough that they’re on call. For example, Bob Seger calls Tulsa and gets my drummer and keeps him for five years to do four platinum albums that he’s on. Then he comes back to Tulsa and goes back to work for me because they’re used to playing with top dogs when they go out, and they want to play with the top cat in town. And even though we’re not making big dough, this is a legitimate act. This band can play anywhere in America and get people off, and open for anybody, or headline a show. I’ve always said it wouldn’t embarrass me at all to walk on stage with The Eagles or anybody, and sing with them. I’ve shared the stage with Leon [Russell], you know, singing “Amazing Grace” where he’d sing a verse and I’d sing a verse. Why, I just had people standing on their seats. I’ve known Chuck Berry for a long time and worked with him, and sang with Wilson Pickett and scream out a line. So I guess what I’m saying is I’m not intimidated, and simply because I’ve played with the top dogs and I know how it’s supposed to be done. It’s given me what I call “creative conceit.” I’m not egotistical about what I do but I know what kind of guns I’m packing and I feel like I can carry the mail. If I want to get on stage with The Rolling Stones or anybody I don’t feel like I’d embarrass myself or anybody else. Now Bonnie Raitt, she’d heard of me a long time before she got to meet me. One night she heard me sing two songs, and I had a piece of gum in my mouth at the time. She was behind the drummer and off to the side watching me sing. Now this was the first night I met her, and I went back there and took this gum out of my mouth and said, “I need to put this gum somewhere.” And she said, “I’ll suck the gum out of your mouth. Get over here to me!” I said, “Bonnie! My baby!” [Laughs]

Todoroff: Have mercy! [Laughs] Bill, what was your most memorable gig?

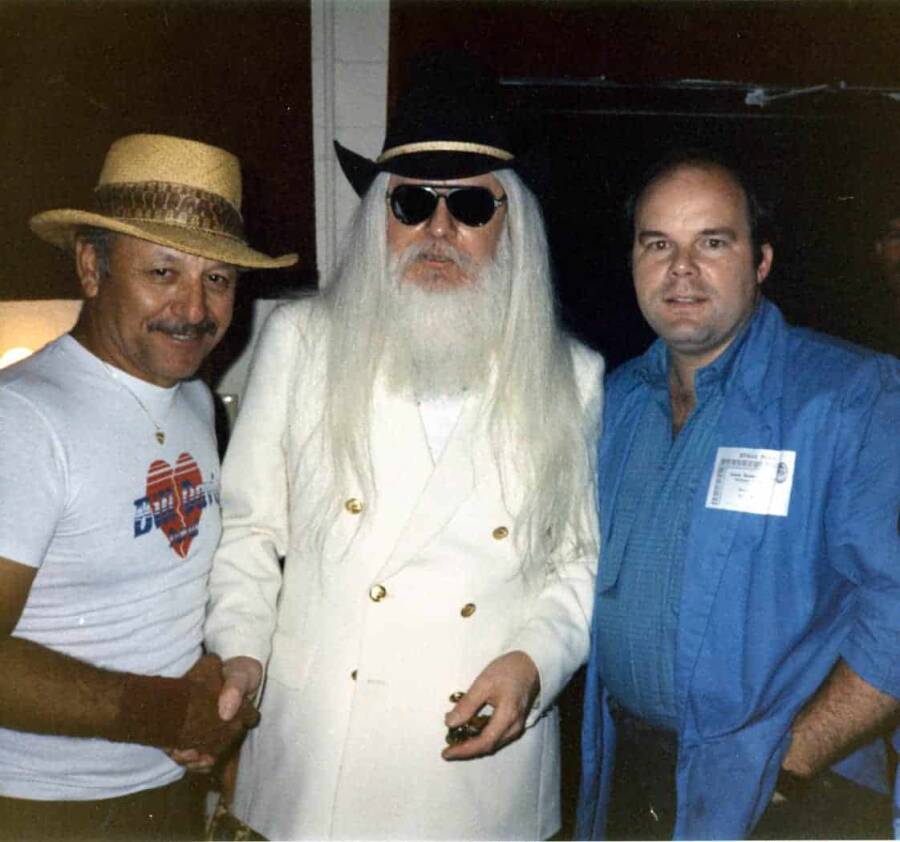

Davis: That show that you produced with me and Leon Russell at the Brady Theater in ’86 was one of the highlights for me. Eighteen hundred people and I had their rapped attention for a ninety minute show. That was pretty unheard of to do that long as an opening act. In fact, some woman wrote in to the newspaper a few days later about “Bill Davis stayed up there too long. Doesn’t know when to get off the stage!” This was like a public forum where you could write into the local paper and some other woman wrote in and said “You don’t know what you’re talking about. Bill Davis knew what he was doing. All of that is picked by the headliner.”

Todoroff: Well, Leon loved it. His band was mesmerized there watching from the side of the stage.

Davis: Leon said, “I need an hour and ten minutes out of you.” So, I gave it to them.

Todoroff: You know, we broke beer sale records at the Brady that night. [Laughs] But I got a lot of positive feedback from people on the show afterward. Even Leon was touched by the crowd’s response.

Davis: Yeah, that was one of those magic nights where everything went off pretty well according to plan. That night, and the first night I played Cains Ballroom, since I was raised right along the same street from that legendary honky-tonk, that was a highlight. The nights I played with Freddie King at P.J.’s Club were very satisfying, because for the first time in my life I was getting feedback from somebody whose music I was doing, and pulling it off. I have lots and lots of black fans that come out to hear the white guy sing their music, so to speak. People say I’m a blues singer, but I always consider myself a “soul” singer. I like to “keen,” you know. Have you ever heard the word “keening?” I like to keen and get those notes going. Blues singers to me are like Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, that’s what I consider a blues singer. And the reason I learned to play harp was to make it sound more authentic. But my idols in singing in black artists were more like Jackie Wilson, Solomon Burke, Ray Charles and those cats. I want to put the “mighty hands of joy” on people and you do it by singing a soul song. You know, “Doggin’ Me Around,” “I’ve Been Lovin’ You Too Long,” etc. To me, that’s more emotional than singing just a stock, three-chord blues song, although that was influential. I just happened to have that voice that I could wrap around those songs that are fun to sing.

Todoroff: I enjoy listening to you sing songs like “Dust My Broom” and “Worried Life Blues.”

Davis: You name it, I can sing it. In fact, that’s one of the things my band is known for, the fact we never rehearse. Everybody in my band has been doing it professionally since they were twenty years old, and we know so many songs that I can just turn around and say something like, “Remember ‘Take Me Back To Georgia’ by Tammy Shaw? Oh yeah, give me a C,” and they’ll give me the C chord and we’ll just do it off the top of our heads and it sounds great. And no rehearsal. Another thing that’s kind of weird with me is the fact I still use that old PA set of mine, like Tommy still uses that old tube amp of his. I haven’t moved up in technology over the years. I’ve got two fifteen-inch speakers and a power amp to drive them and that’s all I use.

Todoroff: You don’t use any monitors or effects either, do you?

Davis: I don’t use monitors. No echo. No reverb. Nothing. Just plug it in and go. That’s why I say my sound check is on/off. I flip the son of a bitch on and if the red light goes on, count off the tune. [Laughs] Just turn it up just loud enough to keep it from feeding back. It’s like a time warp. I’m singing the same songs and using the same equipment that I’ve had for the last twenty years.

Todoroff: I remember seeing you at Aquafest a few years ago and you came out at the end of Jim Byfield’s set and sang “Back In The U.S.S.R.” It was too good. I wish I would have made a tape of that. You came out on stage with your bandana on and your tank top, T-bar shorts, and sunglasses. It sent chills up and down my spine.

Davis: Well rock and roll hoochie-coo! [Laughs] I always feel that in an audience, too. When I walk out on a stage and start singing it feels like everything just goes up a little bit, you know, everybody starts getting a little antsy.

Todoroff: Well, Byfield’s set was great, don’t get me wrong, but when you came out there everything just seemed to kick into high gear. My wife Kathy looked at me, and the people we were with looked over at me and I said, “We’re gonna rock now!” [Laughs]

Davis: Well, Oldaker calls me the “old dude.” See, I’ve got a picture of a band that played in Bixby in 1968 in that old rock gymnasium. You know the one.

Todoroff: Yeah, I spent many a day there held captive in the school yard.

Davis: We played in there, and it was Oldaker on drums, Dick Simms on organ and pedal bass and Steve Hickerson playing guitar. I’ve got a picture of me singing with this band in the old Bixby High School gymnasium. Of course, it wasn’t too many years after that when Simms and Oldaker went on to join Eric Clapton’s band. Anyway, I’ve known Oldaker so long he calls me the “old dude.”

Todoroff: You’ve had an interesting career, Bill, and it’s a long way from being over.

Davis: Well, I sometimes think it was a waste. That I should have applied myself and tried to do a little more than I have with my talent, but all in all I’ve been there when it counted. And I’ve seen a lot of bands come and go, and a lot of guys come and go. Guys would go out to California to make it big, and come back disillusioned, broke and end up quitting the whole deal. I just kept on playing. I’m proud of that fact. I love this town and I don’t ever plan on leaving!

©1990 by Steve Todoroff

Bill Davis….The absolute, best singer on the planet ! ! !

We loved his voice too! The Best!

That was a fun read!

We agree!

SO many warm fuzzy feelings/memories come to mind growing up watching musicians like Bill do their “thang” in the clubs & events in & around our beloved Tulsa. We lived thru the best of the best, the extraordinarily talented musicians male & female.

What I wouldn’t give to experience one more night at the Nine of Cups, the Sunset Grill or the Paradise Club. I only wish I’d have known Bill, having seen him around town & at where I worked occasionally.

Kudos to Steve for doing all he’s done for the posterity of Tulsa music. Keeping the memory of Bill along w/ all the other great Tulsa musicians, producers & of course the MOSAT is priceless. We love you Church Studio. wink wink

Lanette, thank you for your comment. You have always supported all things Tulsa music and the church! We love you!

Thank you Steve for writing about the influential Bill Davis. I learned about everything I know from watching him and his band play when I was an up and coming bluesman. Bill was a very dear friend and I loved him and will miss him. I am honored to have released his ultimate Tulsa Sound Cd “Bill Davis / Same Old Blues.”

I was wondering: A group of businessmen financed the making of a record in the mid to late 70s.

The singer was a Bill Davis. It was cut at Derrick Studios.

Name of the song was “Millionaire Rock and Roll Man.”

Produced by Darrel Price. It mentioned Joplin in the lyrics (which I wrote). I was just wondering if it was the same Bill Davis.